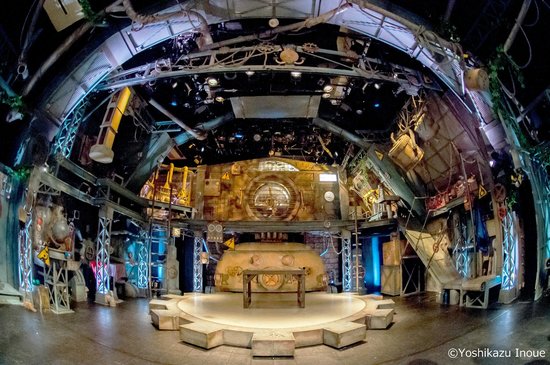

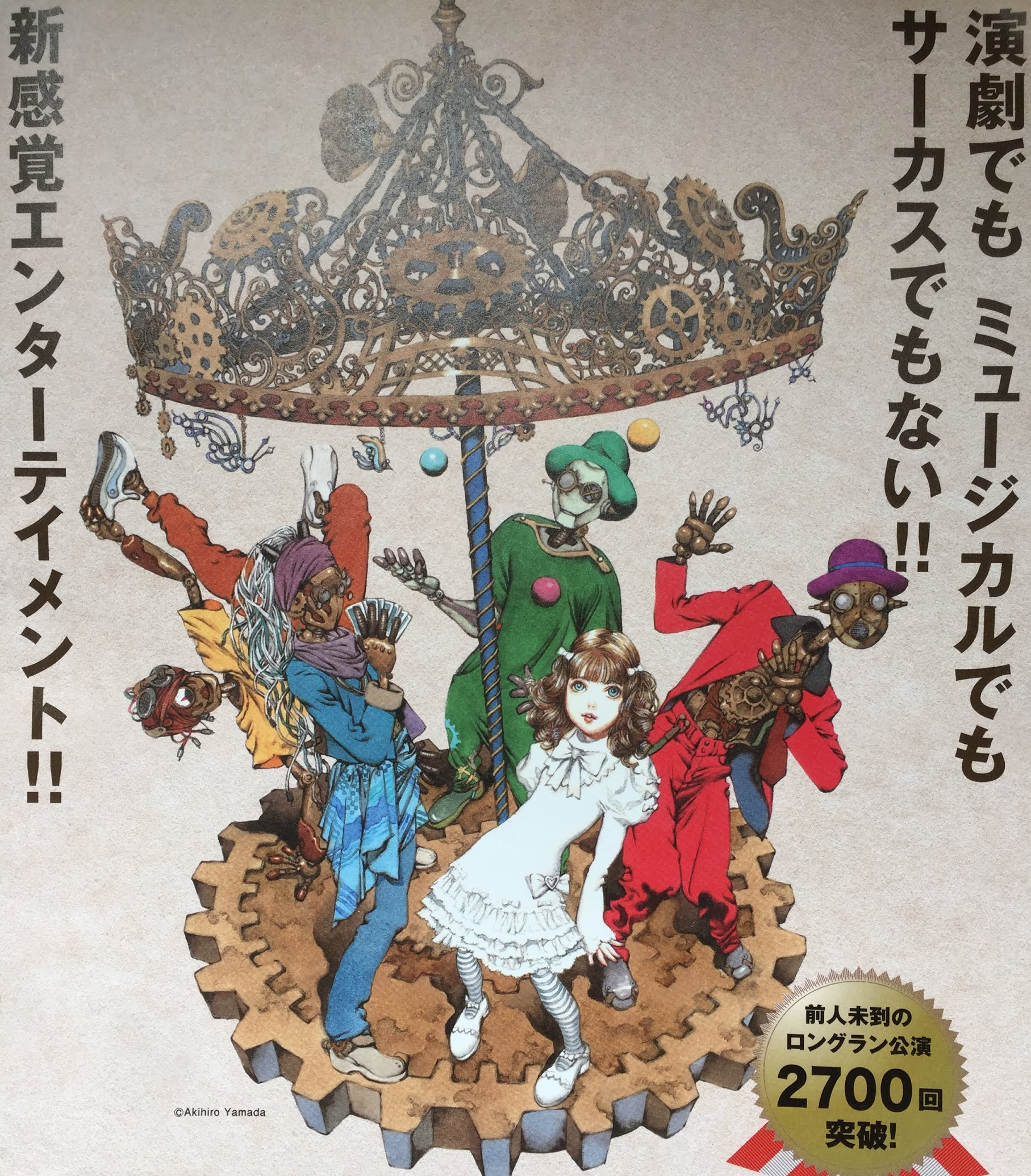

I can’t say that I’ve been to many plays in the past, but when I think theater, I expect Shakespearean plotlines with a protagonist/antagonist combo, the changing of scenery, and large casts. GEAR, performed on the third floor of the Art Complex 1928 in Kyoto, had none of these elements. What I got instead was a novel fusion of a wide array of modern performance elements nestled within a traditional Japanese story arc much unlike what I’ve seen prior. The performance took a very traditional style of theater – nonverbal performance on a single set with a traditional Japanese story arc of impermanence – and brought the art form into modern culture through a use of a futuristic story setting as well as modern dance, music, lighting effects, an elaborate stage, and other entertainment forms not generally seen in theater, to bring classic elements into a production fit for an audience of diverse ages and backgrounds.

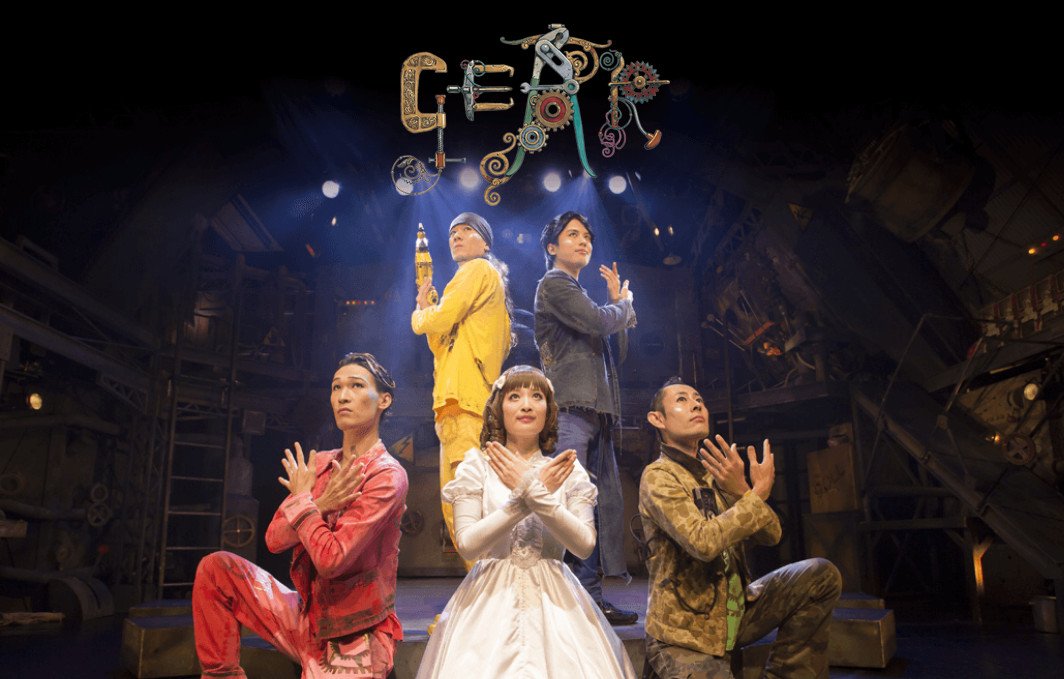

The play establishes the setting through a small amount of narration in the program booklet and a sequence at the start of the play, where four factory robots emerge in a run-down factory clearly no longer in proper production and begin to perform their daily maintenance and production routines – clearly unaware of the futility of their work. They stumble upon a single doll box with the product still inside (evidently the object historically produced in this factory).

The doll is inadvertently unboxed, and a magic trick is performed to seamlessly replace the doll with an actress – the doll having sprung to life in the story in a similar magical manner as to how the inanimate doll was replaced with a person.

The doll resists being put back into the box and begins causing mayhem in the factory as the robots struggle to return her to her box. Through her mischief, she sparks each of the four robot workers, one by one, awakening in them a seemingly newly discovered joy of play. Through these awakenings and corresponding acts by the robots (and eventually one by the doll herself) are heavily accentuated with modern music and elaborate projections and lightshows.

Each worker performs an act dramatically different from each other once they are ‘awakened’. First, the yellow robot erupts into breakdancing alongside a modern soundtrack and a corresponding lightshow that accentuates his actions, as will prove to be the theme for all of the following ‘play sessions’. The next robots all follow the same basic formula – coming in contact with the doll and suddenly bursting out into an act unique to them. The other robots perform acts with miming, juggling and magic. The doll performs the final act with a dance routine heavily accentuated with elaborate lightshows and projections.

Finally, the robot’s and doll’s play go too far. They inadvertently hit a button that causes mayhem and malfunction in the factory as a sort of finale to the show. At the end, the robots are all shut down, and the doll is left alone – overcome with sadness at the loss of her new friends. She attempts to wake them and cries out, but to no avail. She eventually returns to her form as an inanimate object as the next day begins and the robots awaken once more to perform their daily tasks.

The play highlights a common theme in Japanese narratives: mono no aware. It’s a concept that things are more beautiful because of their transient nature – ‘that all good things must come to an end’ to draw an English parallel. The brief period of play and joy was brought to an abrupt and sad end, mirroring a lot of other Japanese narratives and even plays into the emphasis on cherry blossoms, which bloom for only a few weeks out of the year. The short time the doll and robots played highlights the beauty of their circumstance.